Surface Pattern Guide to Entering the World of Art Licensing

J ae Rhim Lee is describing what she would like to happen to her torso after she dies. No simple coffin or cremation for her. Instead, the S Korean creative person is keen to be devoured – which is why she has designed a burying accommodate that, in her ain words, looks similar "ninja pyjamas". Covering every part of her body, the outfit is black with white, branch-like patterns forking downward it. The lining, she goes on to explicate in an intriguing video posted online in 2011, will be filled with mushroom spores that have been "trained" to recognise her every bit food, cheers to having existence fed bits of Lee's shed skin, pilus and nails. Subsequently she dies, she volition be placed in the suit and these cultivated mushrooms will – hopefully – eat her. As she says: "For some of yous, this might be really, really out there."

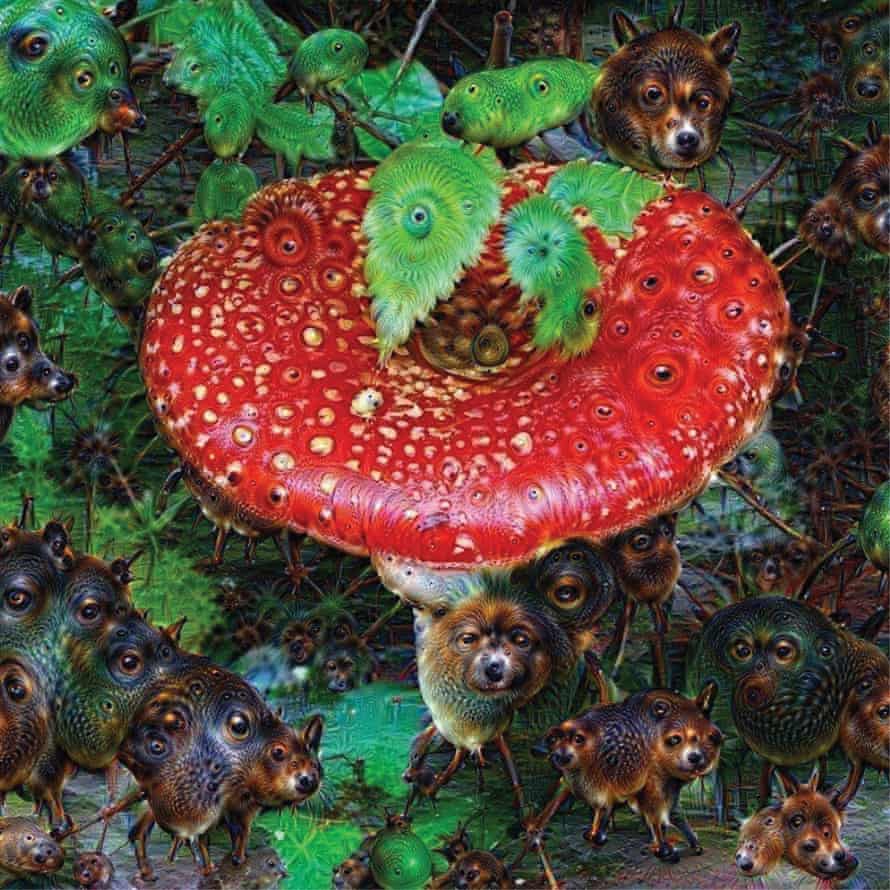

Well, yes. But no more out there than a lot of the strange things on display at Mushrooms: The Fine art, Design and Futurity of Fungi, a new exhibition at Somerset House, London, that aims to show how, over the last few decades, mushrooms have become muses for artists, likewise as useful tools for them to work with. "Mushrooms are playful," says Francesca Gavin, who curated the show and runs the Instagram page @theartofmushrooms. "They're colourful. They remind u.s. of babyhood. They're also delightfully phallic, which is always a pleasure."

"They are neither plants nor animals," says Anne Ratti, a London-based artist who turned her studio into a laboratory to grow magic mushrooms. "They belong to a foreign kingdom of their own. They accept their own way to grow and to reproduce in – and in between – everything. Mushrooms have no borders!"

The show certainly serves up mushrooms in an impressive diversity of ways. British designer Tom Dixon is making a prototype chair out of mycelium, the mass of thin threads that make up the body of a fungus. German conceptual artist Carsten Höller has come with a solar-powered mushroom suitcase. And at that place will be plenty of trippy, psilocybin-inspired visions from the likes of Jeremy Shaw, though Gavin stresses that psychedelia is just one small part of what the mushroom kingdom can offering the art globe. Even the typeface used on the gallery walls was "grown" using an algorithm that mimics fungal growth.

You might retrieve that finding so many mushroom-influenced artists would take quite a bit of foraging, just Gavin says it couldn't have been easier. In fact, this is her 2d mushroom-themed exhibition, a smaller one having already been a success in Paris. She says she could have made this prove much bigger had she wished: "Type in the proper name of any creative person of the last 5 years with the word 'mushroom' and you'll find plenty of work."

One of those artists is David Fenster, who likes mushrooms so much he sometimes dresses as one. His friend, the costume designer EB Brooks, made him an outfit based on the fly amanita (the red toadstool with white speckles that's e'er cropping upwards in children'due south stories such every bit Alice in Wonderland) using a bicycle helmet and insulating wrap.

"I wear the costume as ofttimes as possible," says Fenster. "Like mushrooms themselves, it seems to concenter or repel depending on the private. It definitely gets people's attention – and I think mushrooms deserve our attending. They're overlooked, especially in fungiphobic cultures like ours, which is probably why artists are then interested in them."

Fenster is a film-maker and the costume features in i of his pieces, Wing Amanita, in which the mushroom reflects on the mode information technology's been treated by human being beings over the years. "People used to mix my ancestors in a bowl with milk and put the mixture out to impale flies," it says at i point, earlier bemoaning the way popular culture has warped its public image. "People don't realise that this affair they see in a Mario Bros game is a representation of a real mushroom that really exists!" As Fenster puts it: "I thought it would exist funny to make a film about an anthropomorphised mushroom complaining about how humans have anthropomorphised nature."

Mushrooms have long fascinated artists. In that location are all sorts of examples, from 17th-century Flemish and German language baroque fine art to Victorian fairy paintings, on the Due north American Mycological Association website. Merely fungi have mayhap never been seen as a key muse. A new book, Banquet & Fast: The Fine art of Food in Europe 1500-1800, doesn't even requite them a mention in its index.

Over the last half a century, however, they've provided much nourishment for artistic minds. Cy Twombly painted them; Andy Warhol filmed painter Robert Indiana chomping on one in his 1963 picture show Eat; John Muzzle even co-wrote a book about them, Mushroom Book (1972), which now resides in MoMA'south collection. Muzzle was particularly obsessed – writing mushroom poems, creating mushroom ketchup recipes for Vogue mag and, in 1962, even founding the most recent incarnation of the New York Mycological Guild. "I have come up to the determination that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom," Muzzle explained in the Music Lovers' Field Companion (1954).

Around the turn of the century, I even had my own mushroom mania moment when, writing in the NME, I coined the term shroomadelica: a brusque-lived genre for such bands as the Delays and the Zutons, whose calorie-free psychedelia chimed with the legal loophole that allowed people to ingest magic mushrooms in the UK. Just these examples are mere spores compared with the current boom in mushroom-related art.

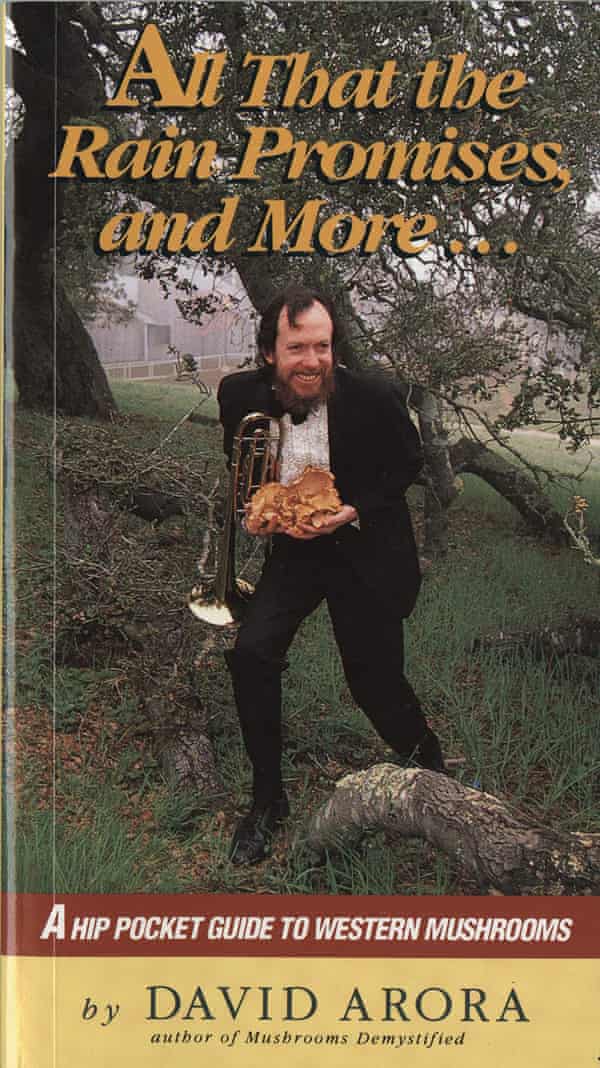

Gavin says that books past Michael Pollan and anthropologist Anna Tsing have been key to turning artists into fungiphiles. Fenster, meanwhile, says he was hooked when he saw the embrace to David Arora'due south 1991 mushroom foraging guide All That the Rain Promises and More. This shows a bearded, slightly crazed-looking human wearing a tuxedo standing in a field property a trumpet and a bunch of mushrooms. The text mixes traditional field guide data with jokes and poetry – and it so enraptured Fenster that he made a film near its writer chosen, fabulously, The Michael Hashemite kingdom of jordan of Mycology (confusingly, there is also a British mycologist called … Michael Jordan).

The show will likewise feature The Mycological Twist, AKA Eloïse Bonneviot and Anne de Boer, who were drawn into the world of mushrooms after reading an article that suggested fungi could interruption down the waste acquired by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. It inspired the pair to look into doing the same in a patch of garden at the London exhibition infinite JupiterWoods. More recent fungal projects include Respawn, a scientific discipline-fiction flick told from the perspective of mushrooms; and Foraging Numberless, an attempt to create portraits of a space'south local ecology using thin fabric bags, mushroom spores and edibles gathered from parks.

"The urgency of the climate crisis is more palpable every day," say the pair over email. "It's hard for an artist to create whatever other work. There's a growing interest in veganism, Extinction Rebellion and cut back single-plastic utilise, and foraging for mushrooms definitely belongs in this list. Considering they are so entangled into ecosystems, they have a potential to be subversives. They remain mysterious, resisting labelling and understanding. They are something you interact with rather than simply use."

Lee'south burial adapt was conceived forth the same lines. She wanted to exist eaten by mushrooms because she was concerned about the many toxins left in our body subsequently we die, from BPA (bisphenol A) picked upward from plastic packaging to the mercury in fillings. The funeral industry is incredibly polluting, delivering toxins dorsum into the environment, yet mushrooms have the power to cleanse. Anyone wearing Lee's suit would accomplish a genuinely green manner of dying.

The more y'all read nearly mushrooms, the more than wormholes you fall down and the more you lot tin see why artists are falling in love with them. Gavin talks enthusiastically about the similarity between mushrooms and the human being brain, and how we have DNA related to them. The Mycological Twist rave near the style mushrooms create networks that allow trees and plants to talk to each other, something known in mycological circles every bit the Wood Wide Web. "That tree in your garden is probably hooked up to a bush several metres away, thanks to mycelia," they say. "These threads act as a kind of underground internet."

Meanwhile, Fenster tells me about the globe'due south largest organism – a mycelial mat that covers more than than 2,000 acres of Oregon's Malheur National Wood – and explains how mushroom spores can survive even in infinite. The heed-blowing facts just keep on coming for these fascinating organisms that can be both beautiful and ugly, nourishing and deadly, intriguing and unknowable.

"What can nosotros larn from them?" says Fenster. "Basically everything. How to be improve humans. How to talk to non-human nature. And how to love ourselves – and the rest of the organisms on the planet."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/feb/02/very-sporish-artists-mad-about-mushrooms-mycology-fungi

0 Response to "Surface Pattern Guide to Entering the World of Art Licensing"

ارسال یک نظر